Architecture reviews

Maintainable technology projects require handoffs between developers, and with new teammates comes fresh perspectives. Building a transparent and remote-friendly workplace is a great start to assist in knowledge transfer, as well as keeping projects as simple and obvious as possible and documenting key decisions.

Simplicity

We’ve done two projects exploring different aspects of simplicity — first, the DATA Act Pilot: Simplicity is Key (2016) project explored the ideas of:

- Building for a least common denominator (CSVs) gave the project reach (more users could participate) and reduced code complexity

- Pulling out validation rules into a separate, easy-to-modify format made the product flexible and simple to maintain

The second explores the idea of simplifying acquisitions in Micro-purchase: Do one thing well (2016) by using code boundaries in projects to define lines between micro-purchases of developer time.

DATA Act Pilot: Simplicity is key

TL;DR

- Select an MVP target; ignore tasks which don’t meet that

- Design for the least capable of your users

- Validation logic should be maintainable outside the source code

Purpose

18F has the pleasure of employing a plethora of truly great software developers. Unfortunately, our project-focus tends to silo our engineers from each other. Rather than wait for knowledge to naturally diffuse through team changes, we can kick-start transfer by highlighting some of the more interesting design decisions from existing projects. Today, we’ll focus on the (completed) DATA Act pilot. Importantly, though that project has finished, this is not meant to be a full retrospective or post-mortem; we’ll be focusing on technical decisions.

As context, the recently minted DATA Act requires agencies generate better, public records around money appropriated from Congress. Treasury has only recently (as of April, 2016) released the final, XBRL (a schema of XML) -based data standard. However, they did not want delays in creating the standard--which caused policy concerns, not technical concerns--to delay the start of agencies’ implementation work. The real hard work for agencies would be around connecting data sources which haven’t been joined before, not around formatting and syntax. Unfortunately, when the agencies hear “XBRL”, they think “contractors”. Rather than planning out how to combine data in house, they plan how to pay someone to generate the appropriate file format. This pilot aimed to remove this excuse by providing a simple interface for agencies to verify that they could combine the data.

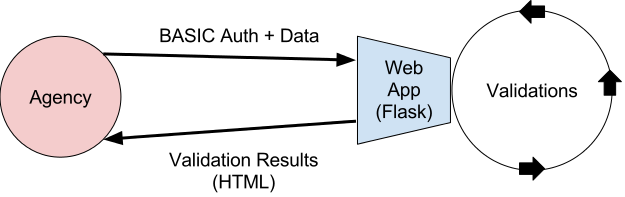

Minimum viable product

While some agencies debated how to make a “data lake” and vendors assembled sales teams to sell DATA Act solutions, the engineers on this pilot focused on a minimal viable product. It would contain two endpoints: one to display a form and one to accept input and report validation errors. There would be no file storage, no authentication (aside from minimal Basic Auth), and no front end build process. They would deploy on cloud.gov and selected a familiar, Flask stack. The team anticipated writing “throwaway” code, a simple demonstration that such an application could exist; they wanted to create that demonstration quickly with few resources. Ultimately, they were quite successful in achieving this goal. The application has been a routine reference point during DATA Act conversations long after the pilot ended.

The proof-of-concept focus had its drawbacks, however. While the team argues that actively ignoring certain best practices was the right choice for many of their decisions, the lack of test coverage would be painful as the project wound down. For example, during this period, they realized that the “happy path” (with no validation errors) caused the application to explode; they had only (manually) run through a handful of scenarios while testing. The team described viewing code as “not real” to be a trap. Their small code base quickly grew larger than anticipated and their early technical decisions would have long lasting ramifications.

Simplicity avoids scary

One of the earliest decisions the team grappled with centered around the data format they would receive from agencies. XML/XBRL was off the table as even a simpler schema would surely trigger the CIO search light. After an initial attempt using Protocol Buffers (“a terrible decision”), they realized they needed something that the folks responsible for the data would understand. Comma Separated Values fit the bill; they aren’t intimidating and are easy to export from existing spreadsheet software and database applications. With them, agencies could focus on finding the data, not encoding it.

Relevant data would be submitted as four separate CSVs, each listing entries for one type of data. Think of it as a very rudimentary (and therefore approachable) set of four RDMS tables, complete with foreign keys. Rather than defining a schema (or waiting for the official schema to be complete), the team generated example CSVs to serve as templates. These were made available, along with the codebase, on GitHub, and would be referenced long after the pilot completed. By defining a set of validations over these files rather than the too-difficult-to-generate-and-not-completely-defined XML schema, agencies could receive feedback about their data now. Further, in the final sprints of the pilot project, the team implemented a simple conversion between the CSV files and the “final” XML/XBRL format, meaning that agencies could continue to work with a format they understood.

Validation rules

Two basic schools of thought dominate discussions of data standards. One holds that data validation should be defined along with the standard. Database schemas include constraints, XML files can be validated against an XSD; by using the sophisticated rules of these and similar languages, one can prevent bad data from entering the system. The second camp argues that the standards are constantly evolving and need to remain flexible, that the validation rules are akin to unit tests for the schema. Further, the language of validation isn’t rich enough to support all of the rules needed. As we will be writing validation rules outside of the data format, why not keep the two separate from the beginning?

With experience of similar problems in industry and knowledge that the XML/XBRL schema was still in flux, the team aligned itself with the second camp. The rules shouldn’t be part of the schema (and couldn’t easily, given CSV input), but they also didn’t want validation logic to live entirely in Python. Requiring developer intervention for all edits would be quite costly, particularly as the rules would be changing over the course of the pilot. If CSVs were a good common denominator for accepting data, perhaps they would be a good format for defining simple validation rules?

| fieldname | required | data_type | field_length | unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AwardandModificationEntryID | False | int | 25 | False |

| PlaceOfPerformanceEntryNumber | False | int | 25 | False |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

This approach proved to be quite handy. It enforced a very clean separation between “business logic” and the rest of the application. It also meant that maintaining these rules as the formal specification changed would be very easy. Editing rules was so easy, in fact, that our agency partner could maintain the rules themselves; they’ve modified these rules over time to fit new expectations. Additional fields could be added and rules applied to them all by simply editing a spreadsheet.

Of course, this scheme doesn’t scale forever. Certain requirements can’t be easily described this way, but these requirements were not encountered over the course of the pilot. The team says that they would have tried to tackle more complex validations in a similar manner, defining the new rule via CSV descriptions. They gained so much value from the approach that they’d work hard to extend it to new problems. When asked how these types of problems are handled in industry, the team pointed to Google’s use of Prolog as a rule engine.

Conclusion

Though this pilot had a very tight focus, it offers several interesting technical decisions which are worth sharing. Determining, at the outset, what a minimum viable product looked like and avoiding “production-ready” concerns like server load, malicious users, etc. allowed the team to exceed their client’s expectations in short order. Building for a least common denominator (CSVs) gave the project reach (more users could participate) and reduced code complexity. Pulling out validation rules into a separate, easy-to-modify format made the product flexible and simple to maintain. Do any of these principles make sense for your project?

This document is the distillation of an architecture discussion between Aaron Borden, Jacob Kaplan-Moss, CM Lubinski, Micah Saul, Marco Segreto, and Becky Sweger. See more information about the DATA Act pilot and the screencasts.

Micro-purchase: Do one thing well

TL;DR

- Use many, focused objects for ease of testing

- Put analogous functionality in analogous file locations

- Pull out core logic into libraries to service multiple interfaces

- Apply best practices everywhere, including JS and tests

Our purpose

Though we pride ourselves on our transparent and remote-friendly workplace, our project focus tends to inadvertently silo engineers from each other. Rather than wait for knowledge to naturally diffuse through team changes, we try to kick-start this transfer through shared interest groups, tech talks, and documents highlighting some of the more interesting design decisions our developers have made. Today, we’ll focus on some of the core architectural philosophies behind the Micro-purchase project.

Contracting for software is often an arduous process; we wanted to make this easier. More specifically, we wanted to create an online marketplace for contributors to 18F open source projects. Though it’s passed through many forms (including a proof-of-concept Google form, a Ruby Sinatra app, and the current Ruby on Rails app), we have effectively built powerful, custom auction software, complete with bidding restrictions, access control, and an admin panel. Along the way, we’ve taken a strong stance on the topic of responsibility: we want each object to be responsible for one chunk of logic -- to do one thing well.

Lonely models, views, and controllers

Rails takes a very strong stance on the separation of models (i.e. data), views (i.e. markup), and controllers (which translate user actions into data manipulations). Often, this leads to so called “fat” models, “skinny” controllers and “thin” views, meaning the majority of the business logic lives within the models. In this architecture, models are responsible not just for loading/querying data, but also handling data transforms, encoding business logic and state transitions, etc. Models have too many responsibilities.

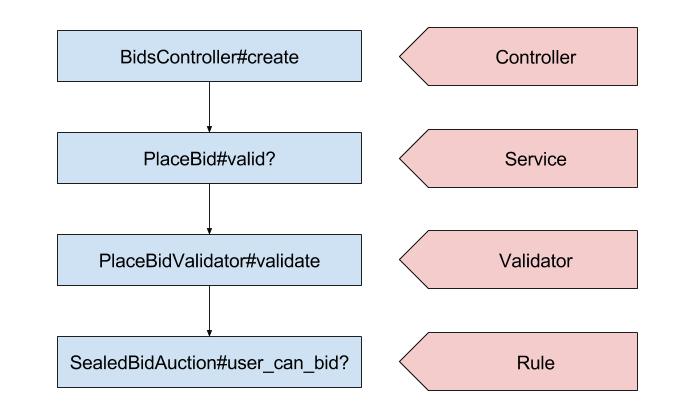

A better strategy is to give each component a single responsibility. Rather than add scoped queries to our models, we add Query Objects, which encapsulate the exact query parameters we need. Rather than placing business logic within models or controllers, we use Service Objects, which each handle a major function of the application. Instead of including complicated logic in the controllers and implicitly passing the results to the view, View Objects provide clear interfaces which define the methods we can use when rendering.

This approach leads to dozens of small, “plain old ruby objects” (POROs). Each fits a specific role (such as “validator,” “parser,” or “presenter”) but only handles that one function. This makes testing very straight-forward; specific logic means fewer code branches. Further, objects of the same role share a similar position within the repository tree and class name, creating a form of standardization across the project.

| Repository | Lines of Ruby | Ruby File Count | Avg Lines per File |

|---|---|---|---|

| C2 | 24549 | 561 | 44 |

| dolores-landingham | 2957 | 106 | 28 |

| identity-idp | 11696 | 200 | 58 |

| open-data-maker | 5482 | 63 | 87 |

| micropurchase | 11136 | 290 | 38 |

Examples: View-, Service-, Rule- and Null Objects

In our app, different users should see different content, including slightly different chunks of markup. “Guests” receive a welcome message while normal users won’t, for example. We could program that sort of logic into the view (i.e. markup template) or add the logic in the relevant controller, but both approaches would be difficult to maintain and particularly challenging to test. Instead, we create “View Objects”, POROs with very clear interfaces for exclusive use within views; they also contain the logic relevant to permission checking, markup selection, etc. Combined, the clean interface and focused logic resolve our troubles around testability.

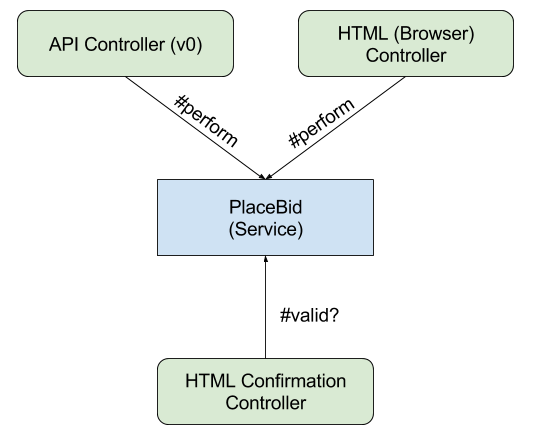

As we’ll describe in detail later, there’s also a need to surface the same functionality through multiple interfaces (e.g. browsers and multiple versions of an HTTP API). Adding that logic to a controller or view is not an appropriate choice. In addition to the reasons mentioned above, this approach limits reusability: each of the interfaces would need to call into that controller or inherit from it. Placing the logic in our models is also not ideal, as most of these actions involve multiple models. Here, “Service Objects” provide a cleaner alternative. They pull the functionality into separate libraries which can be referenced by multiple user interfaces. Further, as each object is responsible for exactly one action, we can list the major functions of our app by listing a single directory.

Let us finally consider how these POROs compose. Individual auctions will have different business rules: some may only apply to small businesses, some may allow multiple bids, etc. Each auction has a combination of these traits; we might naively implement this through classical object-oriented inheritance, but such an approach isn’t feasible and leads to a combinatorial explosion as new options are added over time. We could encode each bit of logic with a switch-case/if-else; this makes finding the logic easy but explodes the size of our classes. To account for both problems, we represent rules as POROs. Auctions defer to their specific combination of rules, which are each represented by this single-purpose “Rule” object. We also make routine use of dedicated "NullObject” classes, which eliminate the need to explicitly check if an object is nil -- for instance, a NullBid object with similar methods to the Bid model is returned when the auction’s winning bid is not available. Do you notice the trend?

Population control

As with any design decision, the PORO approach has trade-offs. While we gain laser focus, it can be difficult to find the objects most relevant to day-to-day maintenance/feature building. With multiple levels of wrapping, delegation, and indirection, we might need to hop through several files before we figure out where certain functionality is defined. Similarly, a single pull request might change 15+ files to add a small feature. These levels also make determining object types challenging: is this auction variable an ORM record? A View Model? A Service? Stack this with rail’s implicit imports and our naming scheme becomes ever more important.

Though still a pain point, we have several strategies for mitigating these issues. Obviously, familiarity with the code base and similar practices on other projects reduces confusion substantially, but we have a few other tricks. We try to name classes consistently (e.g. “DcTimePresenter”, “SamStatusPresenter”, etc.) to encode their function, though the resolve to do that thoroughly has waned. More importantly, classes that perform the same “role” are grouped together within the code base. All presenters live in a folder separate from all serializers separate from all validators, and so forth. Knowing what role you are looking for, then, gives you a big clue as to where to find it.

We’ve also considered some alternative solutions to this organization problem. Ruby’s namespaces might help, but we’ve been bit by unexpected application outages due to the interplay between namespaces and Rails’ automatic path inclusion. An inverted approach, where presenters, decorators, etc. are organized first by a shared data type wouldn’t work for this particular application, as the logic is too tightly bound. That said, we may split the admin interface off into a separate module using this strategy in the future.

+ controllers

+ models

+ ...

+ presenters

| - currency.rb

| ...

+ serializers

| - auction_serializer.rb

| ...

+ services

| - check_payment.rb

| ...

+ validators

| - duns_number_validator.rb

| ...

+ view_models

| - auction_list_item.rb

| ...

+ ...

Different APIs, same solution

The Micropurchase app has been built with multiple consumers in mind. The majority of our existing users are browser-based, meaning that they navigate the system’s user interface through Chrome, Edge, Firefox, et al, placing bids by clicking buttons, typing text, etc. However, we also anticipated (and have realized) API users: those who access our system via automated tools. For example, vendors may want to be notified of all auctions within their technical domain, to automatically bid, or perform other non-UI-driven actions. Our challenge is to keep the two interfaces, browser and machine, in sync, so that both have the same capabilities.

The initial solution was to have a single controller handle both types of requests. The controller could perform queries, save new data, etc. but vary the format of response based on the request’s “accepts” header (i.e. content negotiation). If the same endpoint served all requests, we ensured functional parity, or so the thinking went. Unfortunately, the shared controller strategy assumes that there is a direct mapping between the functionality web-browsing and API users want. This is not safe; machines generally want clear compartmentalization while humans want pages to stitch together multiple types of content. Consider pagination, alone; end users typically reject hundreds of results on a single page while API users would generally prefer them. Adding this logic to the controller leads to lots of if-thens and different code paths -- exactly what we wanted to avoid. This becomes even worse when granting the possibility of multiple API versions.

Instead, we want to think about the API as a separate product. We considered writing in an API-first style (where our webapp consumes our completely-distinct API), but decided against this due to startup cost. We didn’t know what the product would be doing, so creating a good API would be difficult. We also didn’t want to manage multiple apps (potentially multiple servers) at the offset. We also rejected developing a single-page app (which would enforce the API vs UI separation) due to compatibility concerns, issues around client-side authentication, and team familiarity with Rails. Our solution? Service Objects! Each interface (web UI, API versions) call into shared Service Objects (which contains all of the shared code); the controller just needs to convert the input/output as appropriate.

Other applications

While we didn’t want to create a single-page app, we knew we’d leverage “progressive enhancement” to make more usable interfaces, particularly around our report system. Progressive enhancement can be a murky topic, however, particularly when applying it to dynamic interfaces. Which logic should live with Rails, which should live in JavaScript, and should any be duplicated? The principle of single responsibility gives us some rules of thumb to help answer this question. Logic specific to an interactive interface (e.g. around sorting results, formatting graphs, etc.) should live in JS as that’s JS’s sole responsibility. Business logic, however, must live within Rails (specifically, the Service Objects) as that’s their raison d'etre. Despite some potential value for API users, the interactive logic doesn’t fit the API’s purpose, so we keep them separate. We must admit to one major risk with this strategy: siloing by discipline often leads to redundant code and more importantly, can harm team morale. Ideally, no developer has single “ownership” over any chunk of code, despite our do-one-thing-well theory.

In the testing realm, the single-responsibility focus has influenced our stance on behavior driven tests. Written in Gherkin syntax, these tests are hypothetically useful to folks who aren’t able to read lower-level tests (i.e. non-developers). Though there’s potential for leveraging these when discussing with bureaucrats in the future, we’re not confident in that pay off. These tests are problematic in large part due to the annoyances of mixing testing and parsing logic. Before we can write a test, we need to define the steps in our Gherkin scenarios, which often requires writing implementations of those steps as well. BDD tests conflate those tasks, which seems at odds with our single-purpose stance. Further, Gherkin lacks established style guides; while we’ve created our own, we continue to be challenged by minor variations in these steps such as “When I sign in” vs “When I log in” vs “I am logged in”. Combine this with our uncertainty around specific value to our users, we are considering removing these tests.

Conclusion

We’ve now seen some of the implications of following a core philosophy throughout a code base. Designing with focused, single-purpose POROs makes testing easy and can standardize a vocabulary within a project. Dozens of small classes can be difficult to navigate, but the approach works with a diligent team. In particular, placing core application functionality in separate libraries makes supporting multiple interfaces a snap. We’ve also discussed how this principle can be applied to the division between front-end and back-end as well as BDD-style testing. We ask you now, do your modules each do one thing this well?

This document is the distillation of an architecture discussion between Alan deLevie, Jacob Harris, Brian Hedberg, CM Lubinski, Atul Varma, and Jessie Young. Many thanks also to Kane Baccigalupi for early technical leadership on the project. See more information about the Micropurchase project, their GitHub repository, and thoughts around limiting technical debt.

Documenting key decisions

Some 18F projects have found success using Architecture Decision Records to capture key decisions and the context to which they were made, with the goal of allowing future project developers to know if a decision should be revisited or not. The decision records are typically stored in the repository alongside the code, using this template. For example:

Engineering

Engineering